Physics Without Beginning or End: The Logical Spiral to Infinity

From Ether to Spacetime and Back

What if Lorentz was right and Einstein was wrong? What if the ether really exists, just not as Victorian physicists imagined? What if quantum mechanics isn't a fundamental description of reality, but merely our inability to see a deeper layer?

These aren't science fiction questions, but legitimate inquiries posed by leading physicists of the 21st century. The history of physics isn't a story of gradually uncovering truth, but a fascinating spiral where "debunked" ideas return in new guises and where the greatest geniuses often fought against the consequences of their own discoveries.

A Story of Searching for Truth

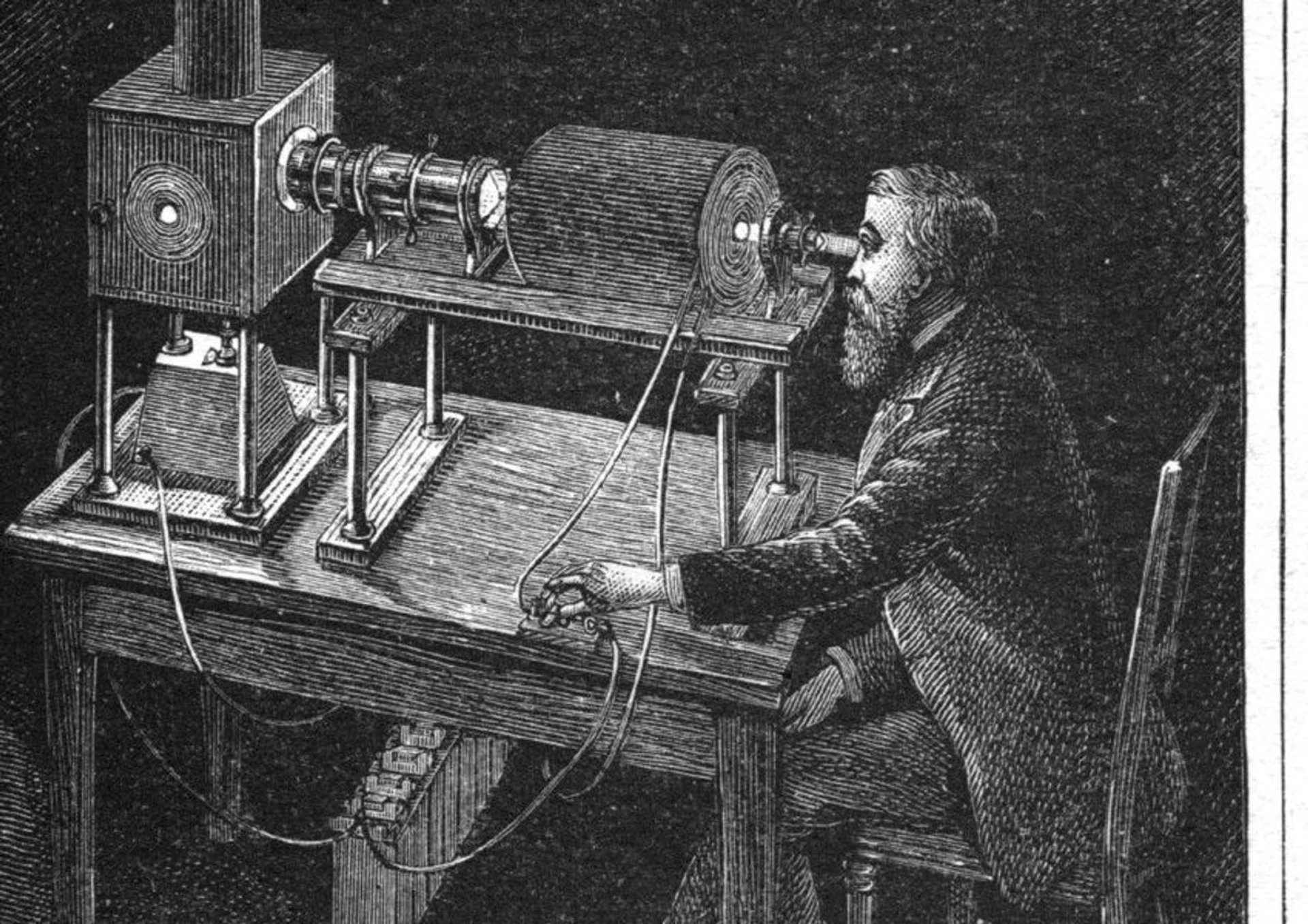

Imagine standing in a laboratory at the end of the 19th century. The air smells of ether (the chemical kind, not the physical one) and all around you are brass instruments, glass flasks, and wire coils. Physics is an almost perfect science. Only a few details remain - minor issues you'll soon resolve. Maxwell's equations have triumphantly unified electricity and magnetism, thermodynamics works like clockwork, and Newton rules the universe with an iron hand. The ether, the omnipresent medium carrying light waves, is as real as the air you breathe. In twenty years, all of this will lie in ruins. And from those ruins will rise a world so strange that Victorian gentlemen would consider it the fevered dream of a drunkard.

All Models Are Wrong, Some Are Useful

George Box once wrote: "All models are wrong, but some are useful." This applies doubly in physics. Every epoch thought it had finally found "the truth" - and every one was wrong. Or perhaps right. Or both simultaneously.

The Triumph of Wave Theory and the Necessity of Ether

From Newton to Young - Light as a Wave

Isaac Newton promoted the corpuscular theory of light - light consists of particles. But in 1801, Thomas Young performed an epochal experiment: he let light pass through two slits and an interference pattern appeared on the screen - alternating bright and dark bands. Only waves that amplify and cancel each other could create this.

Augustin-Jean Fresnel mathematically developed wave theory between 1815-1821 and explained all optical phenomena - refraction, reflection, polarization. When Siméon Denis Poisson objected in 1818 that Fresnel's theory absurdly predicted a bright spot in the center of a circular disc's shadow, François Arago performed the experiment - and the bright spot was there! Wave theory had triumphed.

The Necessity of Ether - Medium for Waves

But waves need a medium. Sound travels through air, water waves through water. What carries light through empty space? Christiaan Huygens proposed the "luminiferous aether" in 1678. After Young and Fresnel, the ether became a necessity.

James Clerk Maxwell sealed it in 1865. His equations unified electricity, magnetism, and light into electromagnetic waves. From the equations emerged the speed of light:

But speed relative to what? There must exist an absolute reference frame - the ether. Maxwell himself worked with the ether as a mechanical medium throughout his "Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field."

The ether had to have paradoxical properties: - Perfectly rigid (for fast transverse light waves) - Perfectly permeable (planets move through it without resistance) - Omnipresent (fills the entire universe)

Physicists accepted it. Lord Kelvin declared that the ether is the only substance we can be certain of - this view was shared by most Victorian physicists who saw the ether as a necessary foundation for understanding electromagnetic phenomena.

Lorentz: Facing the Real Crisis in Physics

At the end of the 19th century, everything was in perfect harmony. Maxwell's equations (1865) unified electricity, magnetism, and light. Wave theory of light had triumphed. The ether as carrier of electromagnetic waves was a logical necessity - after all, every wave needs a medium.

Then came 1887 and the Michelson-Morley experiment. The result was devastating: no ether wind. Earth should have been moving through the ether at 30 km/s (orbital speed), but light behaved as if the ether was absolutely motionless relative to Earth. Later experiments pushed the limit of "ether wind" to extremely small values. This made no sense.

FitzGerald-Lorentz Contraction and Mathematical Rescue (1889-1904)

Hendrik Lorentz faced a real intellectual crisis. George FitzGerald (1889) and independently Lorentz (1892) proposed an ingenious solution: what if motion through the ether physically deforms objects?

They derived the contraction factor. If an object moves with velocity ?math-inlinev?math-inline through the ether, it contracts in the direction of motion:

where the Lorentz factor is:

This precisely explained the null result! The longitudinal arm of the interferometer contracts just enough to compensate for the difference in light travel times.

In 1895 Lorentz introduced the concept of "local time" and first-order effects in ?math-inlinev/c?math-inline . Only in 1904 did he publish the complete form of the transformations:

Henri Poincaré named them "Lorentz transformations" in 1905. Notice something remarkable: even time transforms! Lorentz considered this a mathematical trick, but the equations already contained the relativity of time.

Lorentz wasn't a "mechanic who didn't understand his own equations" - he was a brilliant mind trying to maintain consistency in the physical picture of the world. His ether wasn't a naive notion, but a necessity arising from the wave nature of light.

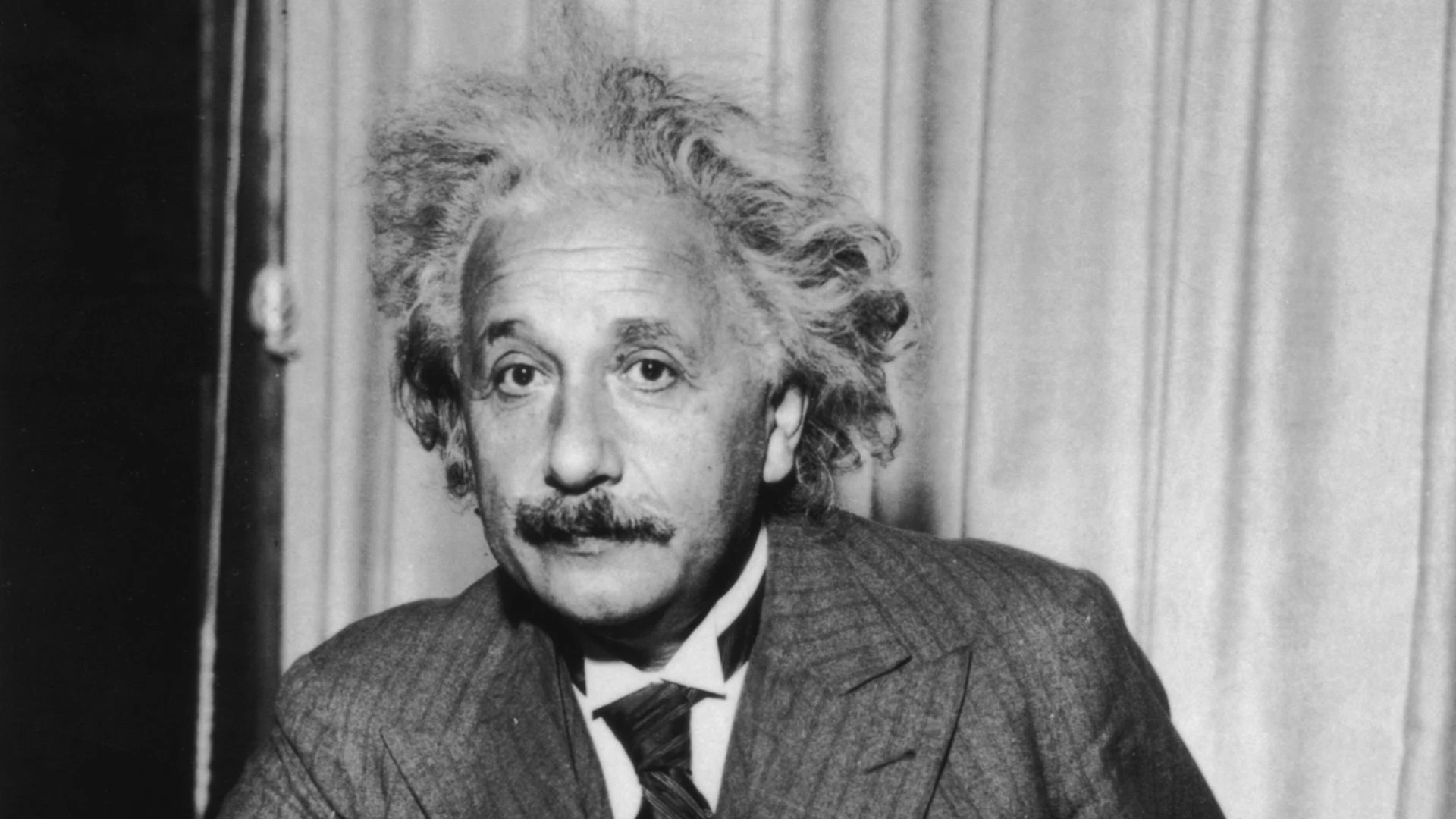

Einstein: Revolutionary Led by Imagination

Einstein never stopped wondering. His greatest discoveries began with simple images in his mind - "Gedankenexperimente" that transformed physics.

Running with Light (1895, age 16)

As a teenager, Einstein imagined running alongside a light beam at the speed of light. What would he see? According to classical physics, he should see a "frozen" electromagnetic wave - light standing still. But Maxwell's equations:

require electromagnetic waves to always move at speed:

This paradox haunted him for ten years.

Special Relativity (1905)

Einstein solved the paradox with two simple postulates: 1. Physical laws are the same in all inertial frames 2. The speed of light is constant for all observers

From this emerged the Lorentz transformations - but with a new interpretation. It's not mechanical deformation in the ether, but the fundamental nature of spacetime.

Train and Lightning - Relativity of Simultaneity

To explain the relativity of simultaneity, Einstein imagined a train traveling at high speed. Lightning strikes simultaneously at the front and rear of the train - simultaneously for an observer on the platform. But a conductor in the middle of the train, moving toward one strike and away from the other, will see them at different times.

Mathematically: The Lorentz transformation of time:

means that events simultaneous in one frame (?math-inlinet_1 = t_2?math-inline ) need not be simultaneous in another (?math-inlinet'_1 \neq t'_2?math-inline ).

Mass and Energy: E = mc²

Einstein derived physics' most famous equation in 1905, but in a way few know. He imagined a box emitting light in opposite directions:

1. Box emits two photons with energy ?math-inlineE/2?math-inline each in opposite directions 2. Each photon carries momentum ?math-inlinep = E/(2c)?math-inline 3. Box remains at rest (momenta cancel) 4. But the box's energy decreased by ?math-inlineE?math-inline 5. From Lorentz transformations, the inertial mass must have decreased by ?math-inline\Delta m = E/c^2?math-inline

Therefore: E = mc²

This equation does NOT say that mass can be simply "converted" to energy as if they were two different things. It says that mass and energy are two sides of the same coin - every rest mass contains energy, every energy has equivalent mass. In nuclear reactions, part of rest mass actually converts to kinetic energy of products (and vice versa in pair production).

Complete Energy-Momentum Equation

Einstein later showed that E = mc² is just a special case of a more general equation:

For a particle at rest (?math-inlinep = 0?math-inline ): ?math-inlineE = mc^2?math-inline For a photon (?math-inlinem = 0?math-inline ): ?math-inlineE = pc?math-inline For a fast particle: the ?math-inlinepc?math-inline term dominates

Falling Elevator (1907) - Equivalence Principle

Einstein later called this thought "the happiest thought of my life":

He imagined a person in a falling elevator. They can't distinguish whether they're falling in a gravitational field or floating in empty space. Mathematically: special relativity applies in a local freely-falling system.

Light in a Falling Elevator (1911)

Imagine a light beam crossing a falling elevator. To an outside observer, the light travels straight, but the elevator accelerates downward meanwhile. For the person in the elevator, the light bends!

According to the equivalence principle: gravity bends light. The bending angle for a body with mass ?math-inlineM?math-inline :

where ?math-inlineb?math-inline is the impact parameter (minimum distance from center). For light just grazing the Sun's edge (?math-inlineb \approx R_{\odot}?math-inline ), the angle comes out ~1.75″. Einstein initially calculated half the value (~0.83″) in 1911; the correct result came only with general relativity.

Rotating Disk (1912)

Einstein imagined a huge rotating disk. The circumference contracts by Lorentz contraction, but the radius doesn't (it's perpendicular to motion). Therefore:

Geometry isn't Euclidean! Space is curved. This led him to the idea that gravity is spacetime curvature.

General Relativity (1915)

After eight years of mathematical effort (with help from Marcel Grossmann and David Hilbert), Einstein arrived at the field equation:

Left side: spacetime curvature (geometry) Right side: energy and momentum (matter)

John Wheeler summarized it: "Matter tells space how to curve. Space tells matter how to move."

EPR Paradox (1935) and Bohm's Reformulation

The original EPR paper works with position and momentum of two particles; the state is prepared so that ?math-inlinex_A - x_B?math-inline and ?math-inlinep_A + p_B?math-inline are sharp. According to quantum mechanics, one cannot simultaneously assign precise position and momentum to a single particle.

EPR considers two alternative runs of the same experiment: - If we choose to measure position at A, we can predict with certainty the position of B without disturbing B (assuming locality). - If we choose to measure momentum at A, we can predict with certainty the momentum of B.

From this, EPR derive a reality criterion: if a quantity's result can be determined with certainty without disturbing the system, there exists a corresponding element of physical reality. According to them, B must have "prepared" values of both quantities, and the wave function description is incomplete.

Einstein called this "spooky action at a distance" (*spukhafte Fernwirkung*), later in letters to Born. The point is the tension between locality and predetermined values.

Today we know from Bell's inequalities that local hidden variables (locality + factorization + standard assumptions) don't work. Yet no-signaling holds — information cannot be sent from A to B faster than light. In quantum field theory, this is ensured by microcausality: local observables at spacelike separation commute.

Bohm's Reformulation (1951) uses a pair of spins in a singlet:

Measuring spin at A instantly determines (predicts) the result at B. The correlations cannot be explained by any local common cause; they result from entanglement from a single preparation.

Bell's Inequality and Its Violation

In 1964, John Bell showed that local realistic theories (with local hidden variables) can be tested. For such theories:

where ?math-inlineS = E(a,b) - E(a,b') + E(a',b) + E(a',b')?math-inline is a combination of correlations.

Quantum mechanics predicts a maximum:

Experiments (Aspect 1982 and others) confirmed the quantum prediction. Nature violates Bell's inequalities, ruling out local hidden variables (under standard assumptions). Important: the "no-signaling" principle remains intact - information still cannot be transmitted faster than light.

What Bell Really Showed

The key understanding is that the whole in Bell's experiment isn't just "A+B". It's "the state of A+B plus our measurement choices plus the apparatus". Bell assumed there exists a joint probability distribution for all possible measurement outcomes - as if particles carried a "cheat sheet" with answers for all possible questions.

But two local answers from one measurement round are just a brief snapshot, not a complete description of the system. We can't replace the whole with a pair of measurements, nor with their series. There's no universal "cheat sheet for all choices" - particles can't carry predetermined answers for all possible questions because each measurement choice is part of the whole.

Violation of Bell's inequalities rules out jointly locality and factorization (local hidden variables). What exactly to sacrifice - locality, "realism", counterfactual definiteness - is a matter of interpretational debates. What's certain is that signals still travel at most at the speed of light. No superluminal information transfer exists.

Bell Test as a "Double-Slit for Two" - Blogosvět.cz

spanel.blogosvet.czForget everything you've heard about quantum "spookiness," instant communication across the entire cosmos, or consciousness creating reality from two different realities (wave vs. quantum). The Bell test—physics' most misunderstood experiment—actually reveals something more precise and beautiful: nature is composed of waves of possibilities, not just the predetermined lists of outcomes. Think of it as a double-slit experiment for two particles. Just as single-particle interference proves waves exist, Bell correlations prove those waves persist even across separated detectors. No magic, no paradox—just waves combining in ways classical physics can't reproduce. The math is straightforward: classical correlations max out at 2, while quantum reaches 2√2, which is precisely the theoretical limit for any information transfer. That's it. Here's the real story, without the myths.

The Power of Visual Imagination

Einstein wasn't just a mathematician - he was a visionary who saw physics in images: light rays as trains of photons, spacetime as elastic fabric, gravity as a depression in a trampoline. When asked how he thought, he answered: "Words do not play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which serve as elements of thought are certain signs and more or less clear images." This ability to "see" abstract concepts was his greatest strength, though perhaps also a limitation - he couldn't accept quantum mechanics precisely because he couldn't visualize it.

The Quantum Revolution: When Reality Exceeded Imagination

Quantum mechanics arose from the conflict between theory and experiment. Max Planck introduced energy quantization in 1900 as a mathematical trick to explain blackbody radiation. Einstein took quanta seriously in 1905 and explained the photoelectric effect. Bohr quantized electron orbits in 1913. Then came an avalanche.

De Broglie proposed in 1924 that particles are also waves. Heisenberg created matrix mechanics in 1925. Schrödinger wrote his wave equation in 1926. Born interpreted the wave function as probability that same year. Heisenberg formulated the uncertainty principle in 1927.

In just 27 years (1900-1927), a theory was born so strange that no one truly understands it to this day, yet so successful that all modern technology rests upon it.

Historical Irony - When Geniuses Reject Their Own Discoveries

Newton: "I Frame No Hypotheses"

Isaac Newton famously declared "Hypotheses non fingo" (I frame no hypotheses) in his Principia. Ironically, his gravity acting instantly at any distance was the boldest hypothesis in the history of physics. Newton himself was disturbed by this "spooky action at a distance" and wrote:

He spent years searching for a mechanical explanation of gravity - ether vortices, particle pressure - but in vain. His followers simply accepted the mathematics and stopped asking "how it works."

Mach: Atomic Blindness

Ernst Mach, whose principle inspired Einstein to general relativity, rejected the existence of atoms until his death (1916). He considered them "metaphysical speculation" and insisted that science should describe only what can be directly observed. Ironically, Einstein in 1905 - eleven years before Mach's death - had theoretically explained Brownian motion as a result of molecular collisions, providing strong evidence for the atomic structure of matter.

Einstein: Father of Quantum Theory Who Rejected It

Einstein laid the foundations of quantum mechanics: - 1905: Photoelectric effect - light consists of particles (photons) - 1916: Stimulated emission - spontaneous quantum jumps with precise statistics - 1924: Support for Bose - quantum statistics

Each of these discoveries contained statistical behavior that Einstein interpreted as incompleteness in our description. Yet Einstein stubbornly insisted that "God doesn't play dice." But note - Einstein didn't reject quantum mechanics as such. He rejected the Copenhagen interpretation, which claims that statistical predictions are all we can know about nature.

And is Einstein definitively wrong? We don't know. Statistical behavior could be: - A consequence of ignorance of a deeper deterministic layer - An emergent property of complex systems - A fundamental limit of our knowledge (not necessarily of nature itself)

Theories like de Broglie-Bohm or Many Worlds are fully deterministic and give the same predictions.

Schrödinger: The Creator Who Regretted

Erwin Schrödinger created the fundamental equation of quantum mechanics (1926):

Ten years later he declared:

His famous cat wasn't an attempt to explain quantum mechanics, but to show its absurdity. Schrödinger believed the wave function describes a real physical wave, not probability. He fought against the Copenhagen interpretation until the end of his life.

Bohr: "There Is No Quantum World"

Niels Bohr, architect of the Copenhagen interpretation, had a paradoxical view of quantum reality. According to Aage Petersen (1963), who worked with Bohr for long, Bohr often said:

(Note: This is a secondary quotation from Petersen about Bohr, not Bohr's direct text.)

Yet today we have quantum computers that evidently "do something" at the quantum level. Bohr might argue that a quantum computer is a macroscopic device producing classical results. But where exactly is the boundary?

Heisenberg: Uncertainty Principle - Fundamental or Epistemic?

Werner Heisenberg formulated his famous principle:

Copenhagen interpretation says: It's a fundamental limit of reality. But other interpretations claim: It's just a limit of our knowledge.

What we know for certain: We'll never be able to simultaneously measure position and momentum precisely.

What we don't know: Whether particles "have" these values and we just can't determine them, or don't "have" them at all.

Heisenberg himself commented enigmatically:

Randomness, Uncertainty, Statistics - What Do We Actually Know?

Quantum mechanics gives statistical predictions, that's an experimental fact. But what does this mean for the nature of reality? The Copenhagen interpretation claims that statistics is all we can know - before measurement, a particle simply "doesn't have" a definite position. But equally valid alternatives exist. In de Broglie-Bohm theory, a particle always has a precise position, we just don't know it, and the wave function deterministically guides it. In the many-worlds interpretation, all possibilities are realized in parallel branches of reality, and statistics arises from our necessarily limited subjective view. QBism goes even further and claims that quantum probabilities are purely subjective, like bets, not objective properties of nature.

Heisenberg uncertainty ?math-inline\Delta x \cdot \Delta p \geq \hbar/2?math-inline is a mathematical fact, but its interpretation remains open. It could be a fundamental limit of reality, as Copenhagen claims. Or just a limit of our knowledge, as hidden variable theories suggest. In some speculative theories with discrete structure of space, it's a natural consequence - you can't measure more precisely than the basic "grain" of reality. Or it's an emergent property of the measurement process, where interaction with the measuring device necessarily disturbs the system.

So what do we know with certainty? We cannot simultaneously measure complementary quantities precisely - all experiments confirm this. Quantum predictions are undeniably statistical. Bell's inequalities are experimentally violated, ruling out local hidden variables. But what we don't know is equally important. We don't know if "randomness" exists fundamentally, or if it's just our ignorance of deeper layers of reality. We don't know if particles have definite values before measurement, or if measurement creates them. And above all, we don't know if beneath quantum statistics lies a deeper deterministic layer that we can't yet describe.

Einstein may not have been right in the specific details of his criticism, but his basic intuition - that behind the statistical description is a deeper, more comprehensible reality - has never been definitively refuted. It's just been pushed aside because "shut up and calculate" works for practical calculations. But working doesn't mean understanding.

Lessons from Irony

The history of physics is full of geniuses who made revolutionary discoveries and then spent years fighting their consequences. Perhaps in that rejection they saw something their followers overlooked. The greatest irony may be that everyone was partially right, just at different levels of description.

Lorentz with his ether may have correctly sensed that space has structure - today we speak of quantum fields, discrete loop geometry, or emergent spacetime. His mechanical ether was perhaps just too concrete an image of a correct abstract intuition. Newton needed an intermediary for gravity and was disturbed by instantaneous action at a distance - today we seek gravitons or describe gravity as spacetime curvature, which are different forms of "mediation". Mach rejected atoms as metaphysics - today we know atoms really aren't fundamental, consisting of quarks held together by gluons, and those may not be the final level either.

Einstein believed in a deeper deterministic layer beneath quantum statistics - theories like de Broglie-Bohm or superdeterminism show this isn't ruled out. Schrödinger insisted the wave function is a real physical wave - in some interpretations he's right. Bohr claimed the quantum world doesn't exist independently of measurement - perhaps he was right that the quantum description is emergent from something more fundamental.

Modern Physics: Equations Without Understanding

The Standard Model of particle physics - the current pinnacle of our knowledge - has 19 free parameters in the version without neutrino masses (with massive neutrinos and their mixing, the number expands to approximately 26). We can't derive them from deeper principles; we must measure them experimentally.

The model works with incredible precision - for example, the agreement between theory and measurement for the g-factor (magnetic moment) of the electron reaches over 10 orders of magnitude precision, one of the most precise agreements between theory and experiment in the history of science. But we still don't know: - Why these particular parameters? - Why these particular symmetries? - What do "virtual particles" mean?

Mathematics works. Intuitive understanding: minimal.

Three Possible Views of Physics History

How should we understand the development of physics? There's a progressive narrative where we gradually approach "truth" - each new theory is a better approximation of reality than the previous one. Newton was good, Einstein better, quantum field theory better still. One day we'll find the final theory of everything. This view has its charm but ignores the fact that "better" often means just "works for more cases", not necessarily "closer to truth".

The instrumentalist view is more pragmatic - theories are just tools for predictions. We don't ask if they're "true", but if they work. Does the Standard Model predict experimental results to 12 decimal places? Excellent, we need nothing more. "Truth" in this view is a meaningless concept - we have only models that work better or worse for different situations.

Perhaps most interesting is a cyclical or spiral model of physics history. We return to old ideas, but at a higher level of understanding. The ether became empty space, which became quantum field, which may become discrete geometry. Particles became waves, then particle-waves, then strings, and perhaps will again become geometry. It's not linear progress but a spiral - we pass through the same themes with deeper understanding.

What if actually nobody had "truth" in an absolute sense? What if Lorentz's mechanical ether and Einstein's curved spacetime are just two different languages describing the same reality? Like when you describe the same landscape in Cartesian or polar coordinates - they look completely different, but it's the same landscape. What if deterministic hidden variables really exist, just not as local properties of particles as Einstein imagined, but as non-local structure of reality? What if quantum "weirdness" isn't a fundamental property of nature, but an artifact of our necessarily limited macroscopic view - like when you look at a hologram from the wrong angle and see only chaos?

Ether: A Story That Doesn't End

The history of ether is a fascinating spiral of physical thought development. In the 19th century, ether was an absolute necessity - the mechanical medium for electromagnetic waves. Einstein "abolished" the ether in 1905 as an unnecessary concept. But quantum field theory brought a new kind of "ether" - vacuum full of virtual particles and quantum fluctuations. Modern theories like loop quantum gravity propose that space has discrete structure at the Planck scale - a different kind of "ether" than mechanical, but still structure filling space. (This line "ether → quantum field → discrete structure" is one possible interpretation of the evolution of physical concepts, not the only consensual view.)

Perhaps Michelson and Morley weren't looking for the wrong thing, just looking the wrong way. They expected mechanical wind in a mechanical medium. The real "ether" - whether it's quantum field, discrete geometry, or emergent spacetime - doesn't manifest as wind because we ourselves are part of it. It's like a fish looking for water - it's immersed so perfectly it can't detect it.

Einstein "abolished" the ether, but his own general relativity gave space dynamic properties - it can curve, ripple, carry energy. That's not passive emptiness, that's an active medium. We just don't call it ether because that word carries the historical burden of mechanical conception.

Conclusion: The Circle Closes

From Lorentz's mechanical ether through Einstein's spacetime geometry to quantum field and perhaps back to discrete structure of reality - physics doesn't advance linearly but in spirals. We return to old questions with new understanding. "Debunked" ideas often return in new, more sophisticated forms.

Those who rejected the consequences of their own discoveries - Newton his action at a distance, Einstein quantum uncertainty, Schrödinger the Copenhagen interpretation - perhaps saw deeper than their followers. Perhaps they intuitively felt that their theories, though mathematically correct, weren't the final description of reality.

Current physics has working mathematics but minimal intuitive understanding. The Standard Model with 19 free parameters works to 12 decimal places, but nobody knows why. String theory operates in 11 dimensions that no one can imagine. Quantum field theory calculates with virtual particles, about which we don't know what they actually are.

Perhaps the greatest lesson from the history of physics is that every generation thought it was close to final understanding. Lord Kelvin in 1900 identified "two small clouds" in physics - not claiming physics was complete, but pointing to specific problems with blackbody radiation and the ether drift. These "clouds" led to relativity and quantum mechanics. Today we have our own "clouds" - dark matter, dark energy, quantum gravity.

21st-century physics may not be about finding the single "correct" theory, but about understanding why different seemingly incompatible descriptions - mechanical ether, geometric spacetime, quantum field, discrete structure - work in different contexts. Perhaps they're just different languages describing the same deeper reality that we can't yet grasp.

As Niels Bohr said: "The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. But the opposite of a profound truth may be another profound truth."

Appendix: Voices on the Ether - A Century of Searching for the Invisible

What Is the Ether?

The ether (luminiferous aether) is a hypothetical medium filling the entire universe that enables the propagation of light waves. It must have these properties: perfect rigidity (to transmit transverse light waves at 300,000 km/s), perfect permeability (planets pass through it without resistance), omnipresence, invisibility and zero mass, yet mechanical properties necessary for wave transmission.

Scientists on the Ether Through Time

James Clerk Maxwell (1878, Encyclopædia Britannica) The ether is a medium capable of transmitting energy; it must have elasticity and finite density.

Lord Kelvin (1884, Wave Theory of Light) "The luminiferous ether is the only substance in dynamics of which we can be certain."

Heinrich Hertz (1890, On the Relations Between Light and Electricity) "Take electricity from the world and light disappears; take the ether and electric and magnetic action can no longer traverse space."

Heinrich Hertz (1894, Principles of Mechanics) "I cannot rid myself of the feeling that these mathematical formulas have an independent existence and intelligence of their own, that they are wiser than we are."

Henri Poincaré (1902, Science and Hypothesis) The ether is a useful hypothesis, but "one day it may be set aside as unnecessary."

Lord Rayleigh (1902) Tests birefringence during motion relative to the ether - negative result. Points to mutually incompatible requirements of different phenomena on ether properties.

Albert Michelson (1903, Light Waves and Their Uses) "If there is any relative motion of Earth with respect to the ether, it must be small." Despite negative results of his experiments, considers the ether the most interesting topic in natural philosophy.

Oliver Lodge (1909, The Ether of Space) "There must always be a connecting medium; truly empty space cannot transmit attraction."

Albert Einstein (1920, Leiden Lecture) "According to the general theory of relativity, space is endowed with physical qualities; in this sense, therefore, an ether exists... Space without ether is unthinkable." (Einstein speaks of spacetime properties, not the 19th-century mechanical ether.)

Paul Dirac (1951, Nature) "With the new theory of electrodynamics we are rather forced to have an ether." (Dirac proposes a relativistic version of ether within alternative electrodynamics.)