Digital Creatures

A Brief Guide to the Origins of Computing

Today, we live in a time when computers are all around us. From powerful mainframes to smartphones in our pockets, digital technology pervades every aspect of our lives. A global network of interconnected computers, vast amounts of recorded information, and machine learning are pushing the boundaries of what is possible and opening up new horizons of knowledge. The journey from simple finger counting to today’s most powerful computers is a testament to human ingenuity and desire for knowledge. Every step has brought humanity closer to a better understanding of the world around us. The digital world we have created is a breathtaking reflection of reality, allowing us to explore, innovate, and communicate in ways our ancestors never dreamed possible.

In the beginning, everything was one number, and that number was infinity. The universe was barren and empty, with zeroes everywhere—except for that infinity. All that exists is part of one unified whole, from which it all originated. Without it, there would be nothing. Let us embark on a journey into the world of zeros and ones—a world that has, in recent decades, transformed into such a powerful mirror of the real universe that our minds often spend more time in this digital realm than in the physical one. Now, let us take a moment to explore the history of this digital revolution.

The very first steps towards understanding numbers and calculations were probably taken by our ancient ancestors when they began to count on their fingers. This simple yet effective method was the earliest tool used for grasping quantity and laid the foundation for developing more complex numerical concepts. Even in prehistoric times, people invented new ways to keep track of quantities. For example, they would carve notches into bones or stones. Archaeologists have found many of these so-called tally sticks, some of which date back tens of thousands of years. These simple tools allowed people to keep count of things like the number of animals they hunted or the days between full moons.

As early civilizations developed, so did more sophisticated computational techniques. The ancient Egyptians used knotted cords to measure distances and land areas. Mesopotamian arithmeticians used hand-made clay objects (“tokens”) of various shapes, each representing different quantities of grain, livestock, or other goods. Over time, people developed more sophisticated methods of counting and recording numbers. The most important was the abacus, the first documented counting machine, dating back to around 2400 BC. Other ancient civilizations, such as the Sumerians and Egyptians, developed their own ways of writing numbers, allowing them to record larger quantities and perform more complex calculations. They created mathematical tables, which included basic calculations, multiplication, and fractions. These tables became essential tools for traders, builders, and clerks.

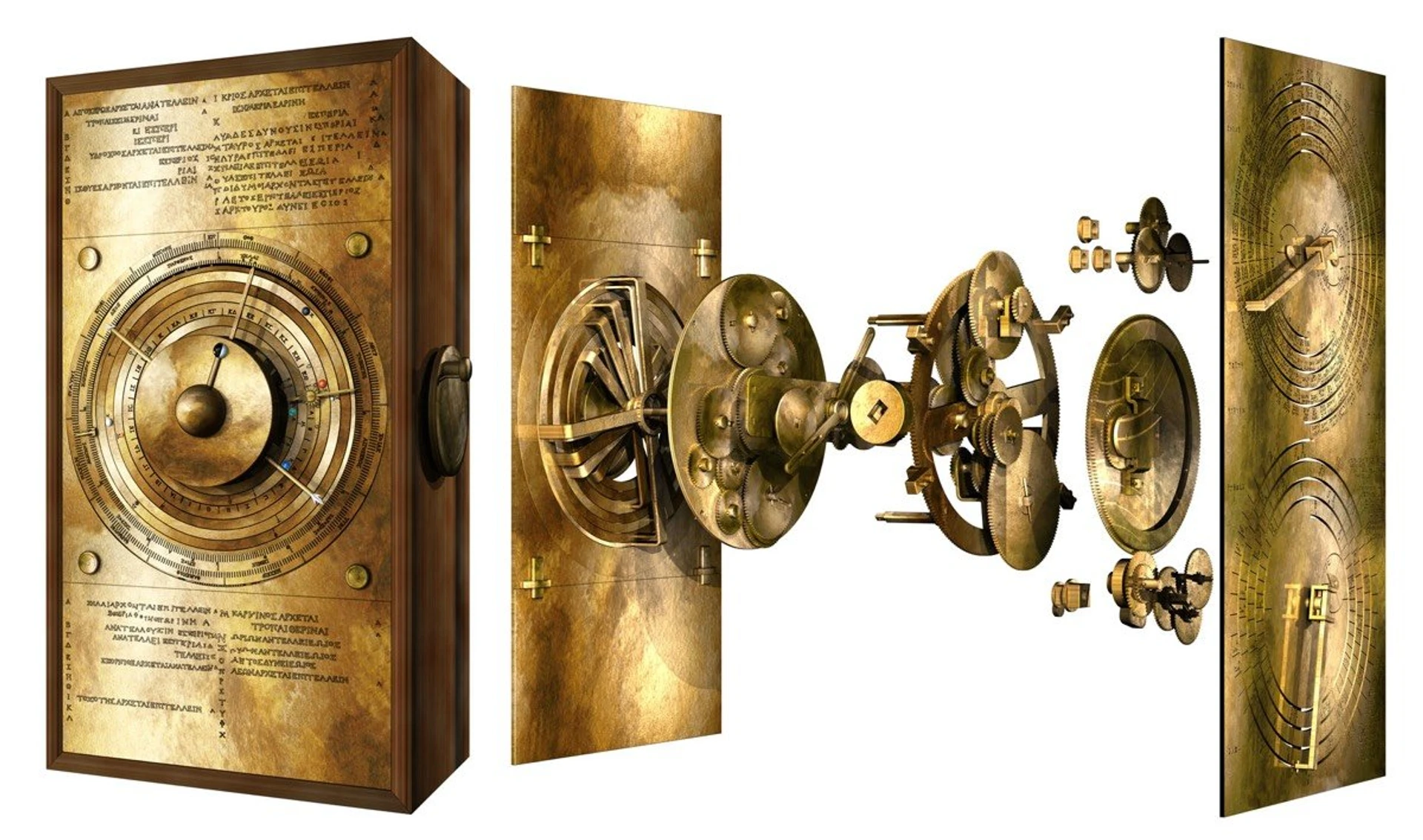

Abacuses have appeared in many different cultures independently of each other. This groundbreaking tool enabled fast and accurate calculations. It was known as suanpan in China, soroban in Japan and schoty in Russia. To this day, this simple yet effective aid is still used in some parts of the world. The ancient Greeks, however, contributed to the evolution of counting devices with much more complex machines—such as the invention of the Antikythera mechanism.

Discovered in the wreckage of an ancient ship dating back to the 2nd century BC, this complex device was used to calculate the positions of celestial bodies and predict eclipses. It is considered one of the first analogue computers in history.

Wonderful New Machines

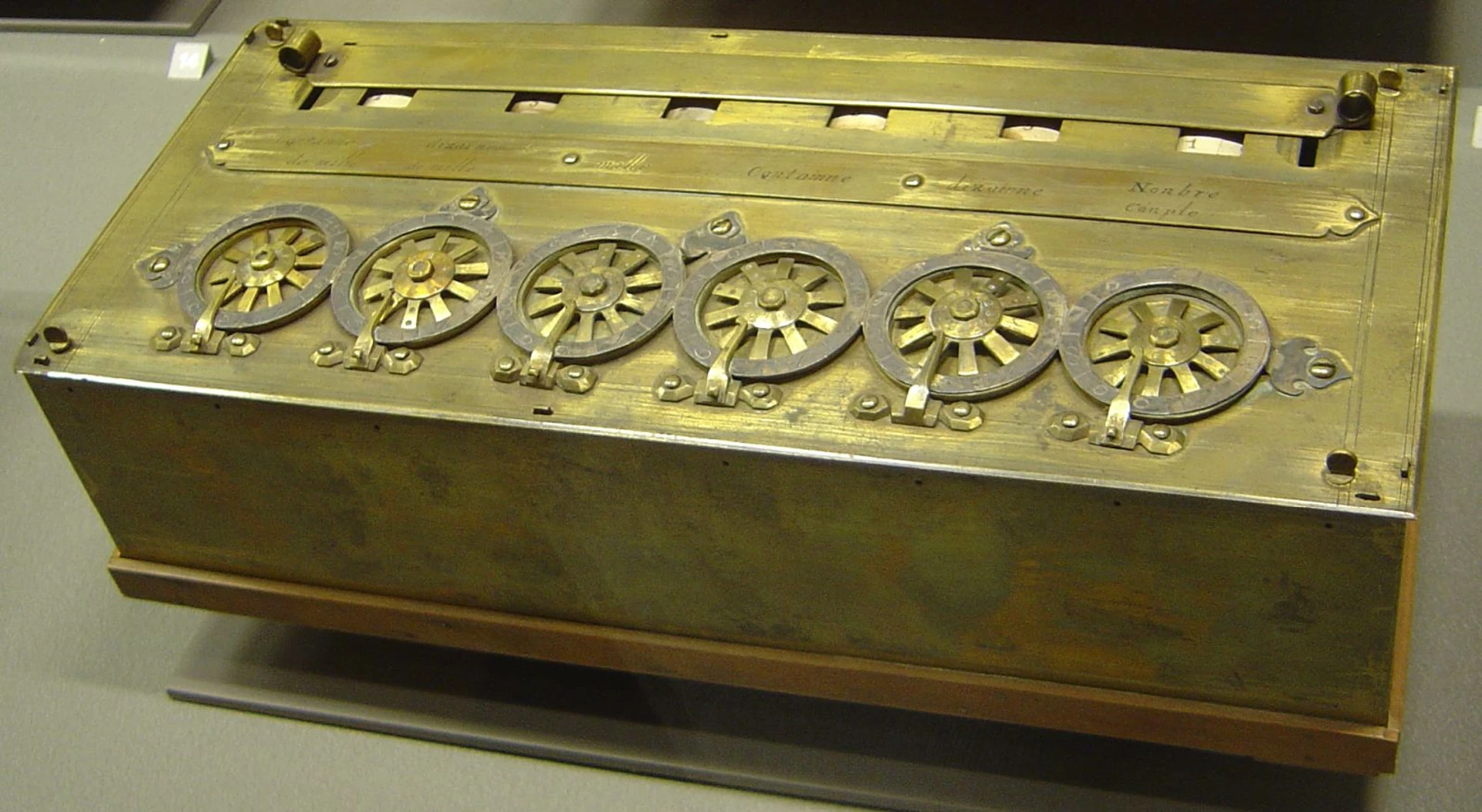

Further advances in computing were made during the Middle Ages with the invention of mechanical calculating machines. A significant milestone was the Pascaline, a mechanical calculator created by Blaise Pascal in the 17th century. This invention could perform both addition and subtraction, which was remarkable for its time. In 1639, Cardinal Richelieu appointed Pascal’s father as the superintendent of Upper Normandy and tasked him with restoring order to the province’s accounts. Blaise Pascal designed the Pascaline to make his father’s job easier. The first version of the machine allowed for the addition and subtraction of two numbers, while multiplication and division could be performed by repeating the addition or subtraction operations. After six years of research and fifty prototypes, Pascal presented his improved machine to the French Chancellor Pierre Séguier in 1645. Over the following decade, around twenty Pascalines were built and continually perfected. Eight of these machines have survived to the present day.

The introduction of the Pascaline marked the starting point for the development of mechanical computing in Europe, which began to extend globally in the mid-19th century. This development continued, among other things, with the invention of the cylindrical gear, which enabled automatic multiplication. The Leibniz calculator, also known as the Stepped Reckoner, was a mechanical calculator invented by the German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. (He first used it in 1673, after presenting a wooden model to the Royal Society of London, and completed it in 1694). Its name derives from the German term for its operating mechanism, Staffelwalze, meaning “stepped drum.” It was the first calculator capable of performing all four basic arithmetic operations. In addition to the tangible calculator, Leibniz also made theoretical contributions to the world of mathematics, notably by formulating the idea of infinitesimal and exploring differential and integral calculus. In 1675, it was he who first introduced the symbol still used today for the integral. The work of Pascal and Leibniz later inspired Thomas de Colmar, who designed the arithmometer in 1820. Based on the principle of manually operated gears and levers, the arithmometer was the first commercially successful mechanical calculator. It preceded more modern mechanical and, later, electronic calculators, and was widely used in commerce, banking, and public administration for most of the 19th and early 20th century. It is estimated that tens of thousands of units were sold. The pinnacle and swan song of mechanical calculators came with the Curta, which remained in production until 1972, when it was finally rendered obsolete by its more sophisticated electronic successors.

The Curta is a mechanical pocket calculator invented by Curt Herzstark (1902–1988) in 1948. It can perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, as well as calculate square roots and execute other operations. Compact enough to fit in the palm of one’s hand, the Curta was considered the best pocket calculator until the 1970s, when it was replaced by electronic calculators. The Curta, however, actually saved its creator’s life. Born to a Catholic mother and a Jewish father, Herzstark was arrested in 1943 and eventually ended up in the Buchenwald concentration camp. While there, the Nazis let him work on developing the calculator, intending to present the finished device to Hitler as a victory gift in World War II.

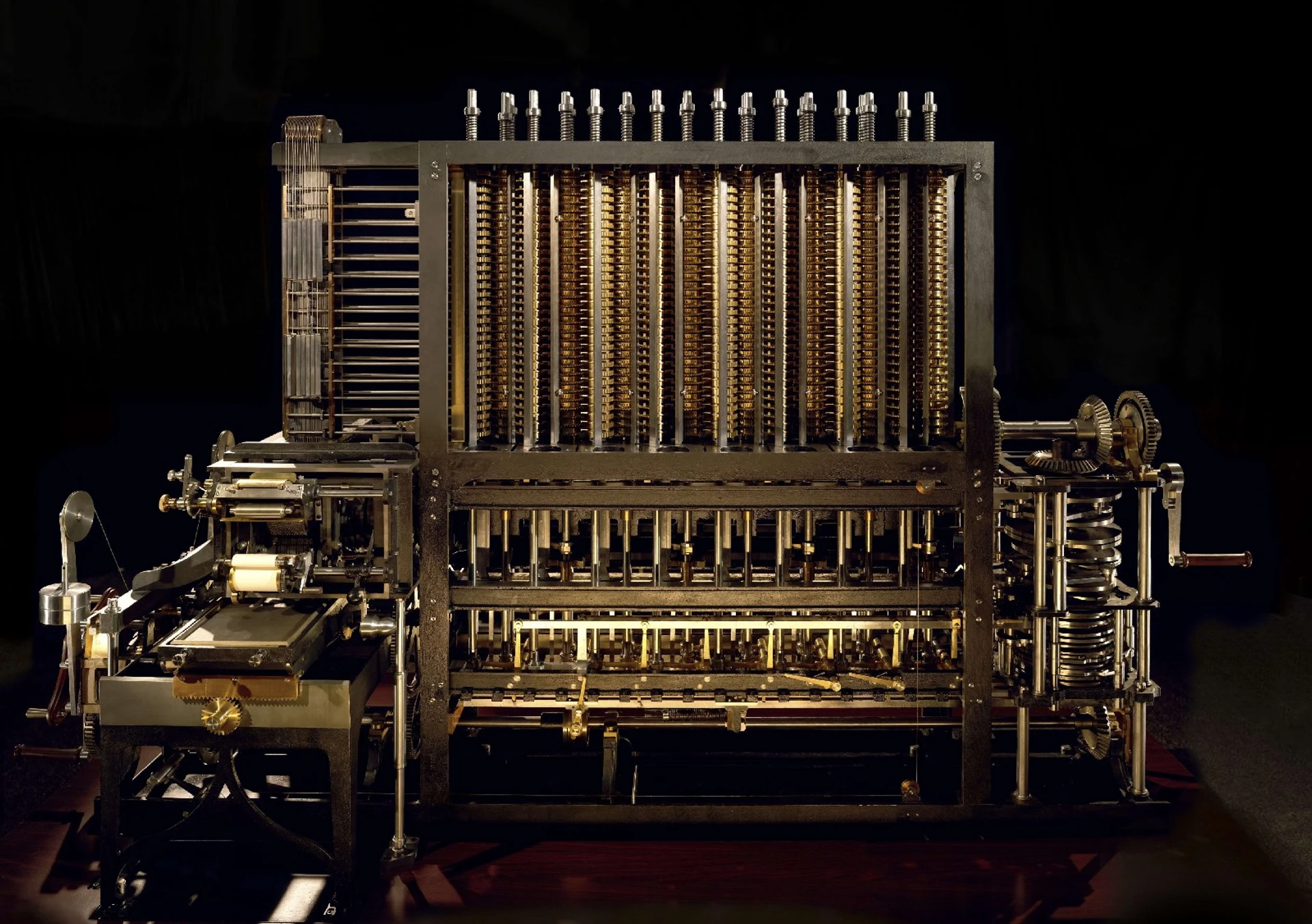

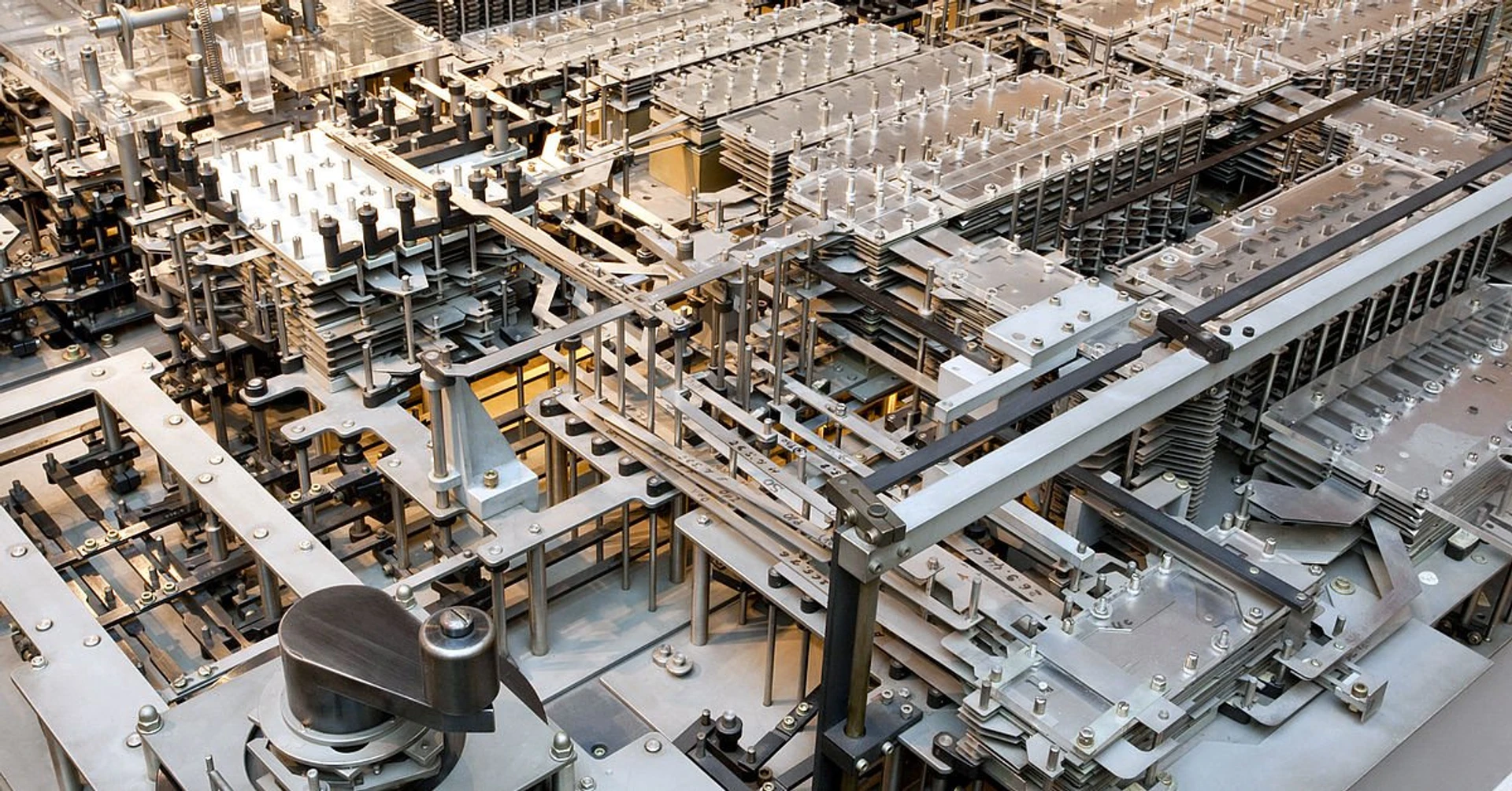

The real turning point in computing history, however, came with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. In the first half of the 19th century, Charles Babbage designed the Difference Engine and later the Analytical Engine, which is considered the true forerunner of modern computers. And while these machines were never built during Babbage’s lifetime, they laid the intellectual foundations for future developments. The Difference Engine was designed with a specific purpose in mind: calculating and printing mathematical tables. The Analytical Engine, however, was intended as a general-purpose computing device, capable of performing various types of calculations. The Difference Engine was mechanically complex but conceptually straightforward. The Analytical Engine, on the other hand, was far more intricate, incorporating elements of modern computers. Working with him on its development was Ada Lovelace, Lord Byron’s daughter. Although she died at just 36 in 1852, she gave birth to three children, predicted the future potential of computers, and became the first female programmer in human history by writing an algorithm for calculating Bernoulli numbers in her treatise on the Analytical Engine. (Though she never tested it herself, modern research has shown that, aside from one error, that is, a bug, the algorithm would have indeed worked.)

Punched Card Era

In 1804, Joseph-Marie Jacquard developed the so-called Jacquard loom, which used punched cards to control the weaving patterns. Drawing on earlier experiments of the 18th century, this invention revolutionized the textile industry by enabling the rapid and flexible production of complex designs, and ultimately inspired the development of information technology. In 1880, Herman Hollerith sought to significantly speed up the processing of census data. Thus, the Electric Tabulating System was born. This ingenious invention used punched cards to store data and electric sensors to read it. Although it might sound simple now, it was revolutionary at the time. Why was it so important? The processing of the 1890 census data took only three months instead of the expected ten years. The machines made fewer errors than the tired clerks and could work with vast amounts of data. Hollerith’s invention laid the foundations for modern computing. His company later became a subsidiary of IBM, and a similar method of data processing was used by the Nazis in their 1930s census. Punched cards remained a standard storage medium well into the 1980s.

In addition to its devastating wars, the 20th century also witnessed the rapid advancement of computer technology: from electromechanical computers to those using vacuum tubes or semiconductors, the technology advanced by leaps and bounds. Each new generation of computers was smaller, faster, and more powerful than the one before it.

In the USA in 1928, L. J. Comrie became the first to use IBM’s punched card machines for scientific purposes, calculating astronomical tables by using the finite difference method, as proposed 100 years earlier by Babbage for his Difference Engine. Soon after, IBM began modifying its tabulators to support such computations. One of these tabulators, constructed in 1931, was the Columbia Difference Tabulator.

In the 1930s, a young engineer named Konrad Zuse lived in Germany. At the age of 26, he began working on a remarkable machine in his parents’ living room. Yes, you read that right—the world’s first computer was constructed in a living room! Zuse was a genius who grew tired of doing complex calculations manually and wanted to create a machine that would handle them for him. Thus, the Z1 (originally called V1, but later renamed to avoid associations with Nazi rockets) was born—the world’s first programmable computer. But don’t picture a sleek laptop or a powerful gaming computer. The Z1, in fact, looked more like a bizarre cabinet-sized blender. It was made up of more than 30,000 metal parts and, just like today’s computers, used binary code (1s and 0s), with data entered via punched film tape.

It had a memory of... a whole 64 words! And while the Z1 wasn’t by any means perfect (as it kept constantly freezing), it laid the groundwork for all the computers that followed. Without the Z1, there might not have been laptops, smartphones, or game consoles. It was followed by the more advanced and fully programmable Z3, which was completed in 1941. The Z3 was the world’s first functional programmable computer, predating similar US and UK projects by several years. It proved that a universal computer could work in practice. Sadly, even the Z3 did not achieve fame, as it was destroyed during the Allied bombing of Berlin in 1943. Due to the isolation of wartime Germany, Zuse’s work remained unknown for a very long time.

And while Konrad Zuse was a successful engineer who went on to live a quiet life, enjoying his fame and living to the ripe old age of 85, a different, perhaps even more important story for the development of computers was unfolding in the UK at the same time—a story that did not involve punched cards.

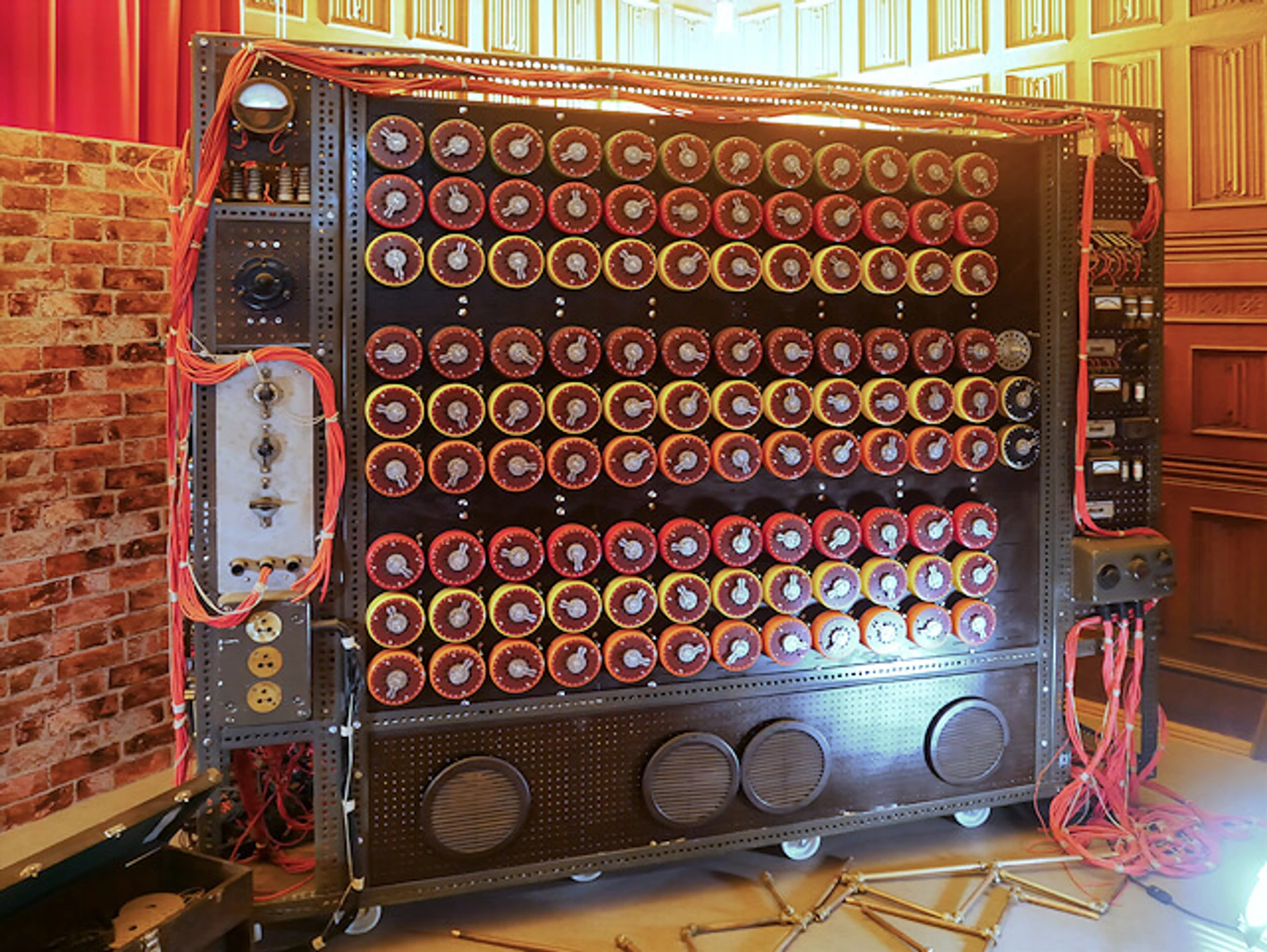

It is the story of a genius who was as successful as he was tragic: Alan Turing. His genius not only helped end World War II but also laid the foundations of modern computing. Turing’s life is a tale of both the triumph of human intellect and personal tragedy. In 1936, Turing introduced his concept of the Turing Machine—a theoretical model that explored the limits of what can be computed. This abstract idea became the basis for the development of all modern computers. During World War II, Turing led a team at Bletchley Park that aimed to crack the German Enigma cipher machine. His work resulted in the creation of the Bombe, a machine capable of decrypting German messages, which contributed significantly to the Allied victory.

After the war, Turing devised his famous Turing Test—a method for determining whether a machine exhibits intelligent behaviour indistinguishable from that of a human. This test has become a cornerstone of AI research. Despite his contributions to both science and national security, Turing’s life ended prematurely. His classmate, close childhood friend, and possibly his lover, Christopher Collan Morcom, died of tuberculosis at just 18. This loss caused Turing great grief, driving him to work even harder on the scientific and mathematical topics the two of them shared. In 1952, he was convicted of “gross indecency” for being in a relationship with another man, which was illegal in the UK at the time. Rather than going to prison, Turing chose chemical castration—a punishment that had devastating effects on his physical and mental health. Two years later, in 1954, Turing was found dead in his home. The cause of death was cyanide poisoning, believed to be suicide.

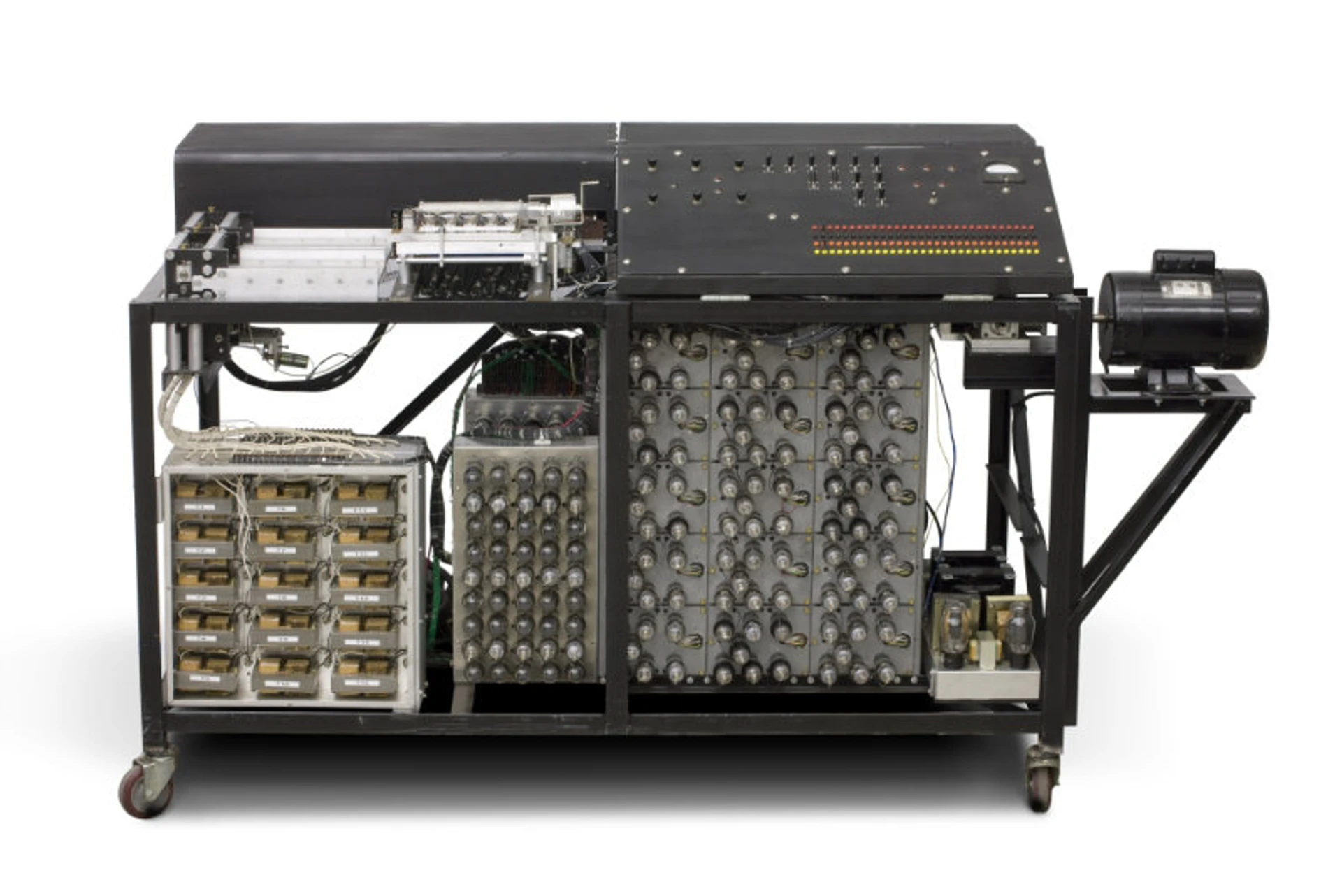

Meanwhile, in early 1937, Howard Aiken was seeking a company to help him design and build his calculator. After two rejections, he was shown a demonstration set donated by Charles Babbage’s son to Harvard University 70 years earlier. This led Aiken to study Babbage’s work and incorporate elements of the Analytical Engine into his own design. The resulting machine brought Babbage’s principles almost to full realization while adding significant new features. Finally, in 1944, amid the turmoil of World War II, the Harvard Mark I was born—the first programmable computer in the United States. Officially known as the IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC), this giant machine, developed through a collaboration between Harvard’s Howard Aiken and IBM engineers, used punched cards as its primary medium. Measuring 15.5 metres long, 2.4 metres high, and weighing over 4,500 kg, the Mark I was an absolute behemoth. Developed and built at IBM’s Endicott plant, the ASCC was delivered to Harvard in February 1944.

While it was not the first functional computer, the Mark I was the first machine to automate complex calculations, marking a major step forward in computing. This electromechanical marvel was built from 765,000 components, including switches, relays, and miles of cables. It could perform three addition or subtraction operations per second; multiplication took six seconds, and division 15 seconds—a feat that may seem ridiculous today but was truly revolutionary at the time. The Mark I was programmed using punched tape, which enabled the automatic execution of sequences of arithmetic operations. This feature was crucial to its primary task: computing ballistic tables for the U.S. Navy during the war. John von Neumann had a team at Los Alamos that used modified IBM punched card machines to calculate the implosion effect. In March 1944, he proposed running specific implosion-related problems on the Harvard Mark I. That year, he and two mathematicians wrote a simulation program that analysed the implosion of the first atomic bomb. In the end, the Los Alamos group completed their work in much less time than the Cambridge group working with the Mark I. The punched card machine, however, calculated values to six decimal places, whereas the Mark I calculated values to 18 decimal places. Moreover, the Mark I integrated the partial differential equation with a much smaller interval size, achieving far greater precision. Although it was soon surpassed by fully electronic computers such as ENIAC, its importance cannot be overstated. It bridged the gap between mechanical calculators and modern electronic computers, showcasing the world the potential of automated computing and inspiring a generation of scientists and engineers to further develop this technology.

Future Belongs to Electronics

Around the same time, during World War II, Colossus—the first fully electronic digital computer—was developed in the UK. Designed in 1943 by Tommy Flowers and his team for MI6 at Bletchley Park, its main purpose was to crack German encryption codes, particularly those generated by the Lorenz SZ40/42 machine used by the German Army High Command. The first Colossus was operational by December 1943 and fully functional by February 1944. In total, ten of these machines were built. Containing about 1,600 vacuum tubes, it was a pioneer in their large-scale use. The machine could process 5,000 characters per second, considerably speeding up the decryption process. Interestingly enough, Colossus may have been a follow-up to a lesser-known machine developed in the dusty labs of Iowa State College (now Iowa State University) in 1939. Though no one knew about it at the time, this machine was destined to change the world: the Atanasoff-Berry Computer, also known as the ABC. It was, in fact, the first electronic digital computer of its kind. Created by John Vincent Atanasoff, a physics professor, and his graduate assistant, Clifford Berry, this revolutionary device was designed with one goal in mind: to solve complex systems of linear equations. While this task may not seem very exciting, the results of their work were truly staggering. The ABC introduced several groundbreaking innovations: it was the first machine to use vacuum tubes for digital computation, to employ a binary system to represent data, and to separate memory and computational units. Its 300 vacuum tubes and regenerative drum memory were the forerunners of the technologies that power today’s smartphones and supercomputers. Ironically, the ABC never achieved widespread recognition during its time. Its development was interrupted by World War II, until it was eventually dismantled. Atanasoff never got his invention patented, leading to decades of legal battles over who invented the first electronic computer. It wasn’t until 1973, long after ENIAC and other more famous early computers were developed, that a court ruled Atanasoff was the true inventor of the very first electronic digital computer. Looking back today, we can see the ABC as a quiet revolutionary. Although it was not programmable in the modern sense and was designed for only one specific task, the principles it introduced became the foundation for all computers that followed.

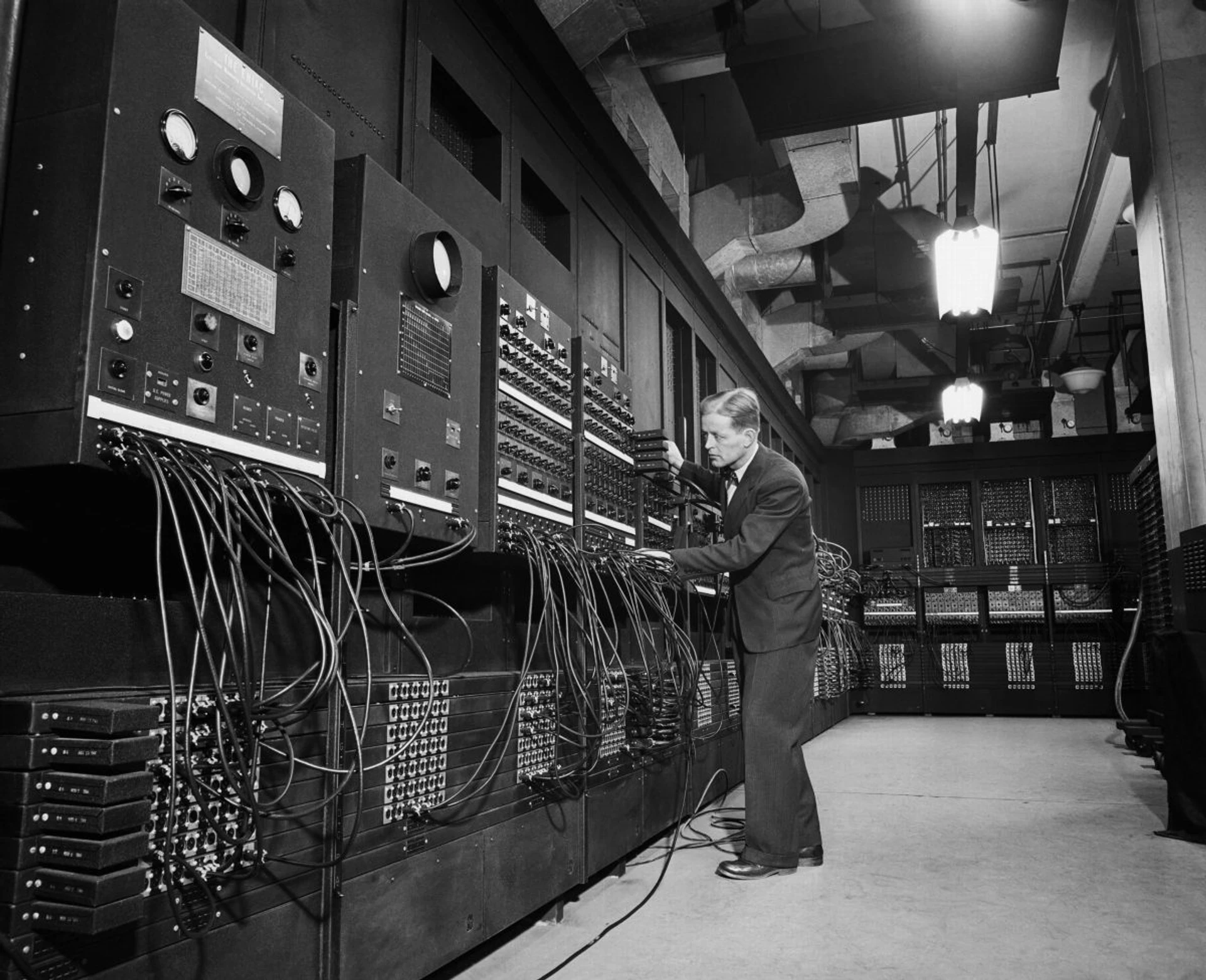

In 1946, as the world was still recovering from World War II, ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was introduced at the University of Pennsylvania. Designed by J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, this machine was a true technological giant, weighing 30 tons, containing 17,468 vacuum tubes, and consuming 150 kilowatts of power. Initially built for the U.S. Army to calculate artillery ballistic tables, its capabilities extended far beyond its original purpose. ENIAC could perform 5,000 additions per second—an unimaginable speed at the time. Programming it, however, was a physical challenge.

Its programmers, often women, had to manually reconfigure cables and set switches for each new calculation. Nevertheless, it opened the door to modern programming and inspired the development of the stored-program concept we still use today. It was more than just another computing machine—ENIAC symbolised a new era, representing the transition from mechanical and electromechanical devices to fully electronic computers.

Another crucial machine from this era was EDSAC (Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator), developed at the University of Cambridge under the direction of Maurice Wilkes. First run on 6 May 1949, EDSAC was the first practical stored-program computer. It used the von Neumann architecture and mercury metal delay-line memory. Programmed using assembly language, EDSAC executed about 650 instructions per second, proving to be an excellent tool for various scientific calculations.

First Computer Generation

In 1951, the UNIVAC I (UNIVersal Automatic Computer I) was introduced as the first commercially produced computer in the U.S., marking the beginning of digital data processing for businesses and government. Although developed by the same visionaries behind ENIAC, the UNIVAC I was designed for broader use in commerce and industry, unlike ENIAC, which was primarily a military tool. Weighing nearly 13 tons and containing over 5,000 vacuum tubes, the UNIVAC I was still quite enormous. Compared to its predecessors, however, it represented a revolution in both compactness and efficiency. It could perform about 1,905 operations per second—an astonishing feat for its time. One of the UNIVAC’s key innovations was the use of magnetic tape for data storage, replacing punched cards.

This dramatically increased the speed and reliability of data storage and retrieval. The UNIVAC I gained fame in 1952 when it correctly predicted Dwight D. Eisenhower’s victory over Adlai Stevenson in the U.S. presidential election—an outcome widely doubted at the time. This event showcased the potential of computers for data analysis to the general public. A total of 46 UNIVAC I systems were built and used by the military, government agencies, and large corporations. Each machine cost more than a million dollars (not adjusted for inflation), which illustrates how rare and valuable this technology was in its early days. The UNIVAC I marked the beginning of an era in which computers became practical tools for everyday use in business and industry. It paved the way for all subsequent generations of commercial computers and laid the groundwork for the digital revolution that continues to shape our world. Soon thereafter came the IBM 701, the first large IBM computer designed for scientific computing, followed by the IBM 650, the first mass-produced computer, just a year later.

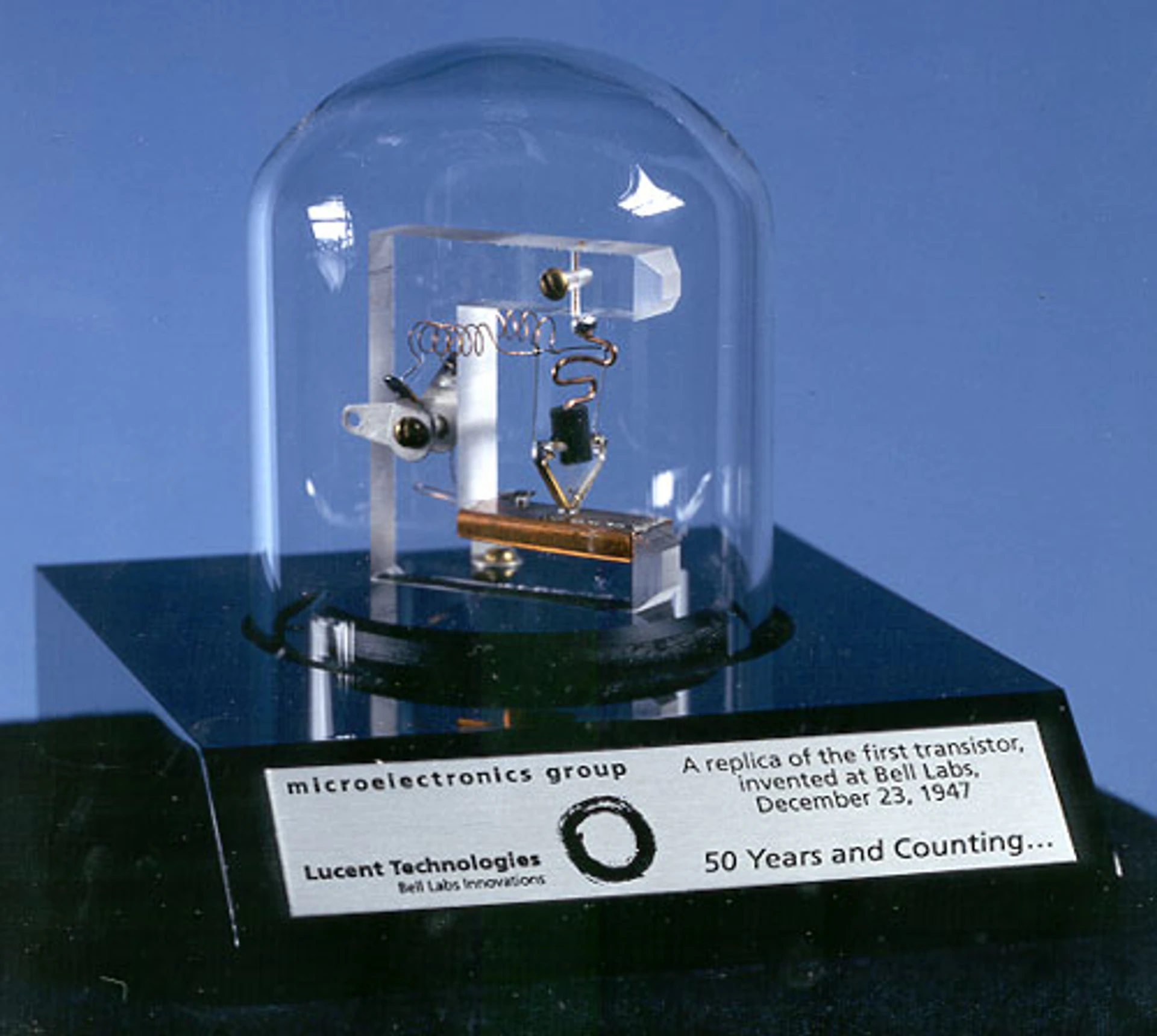

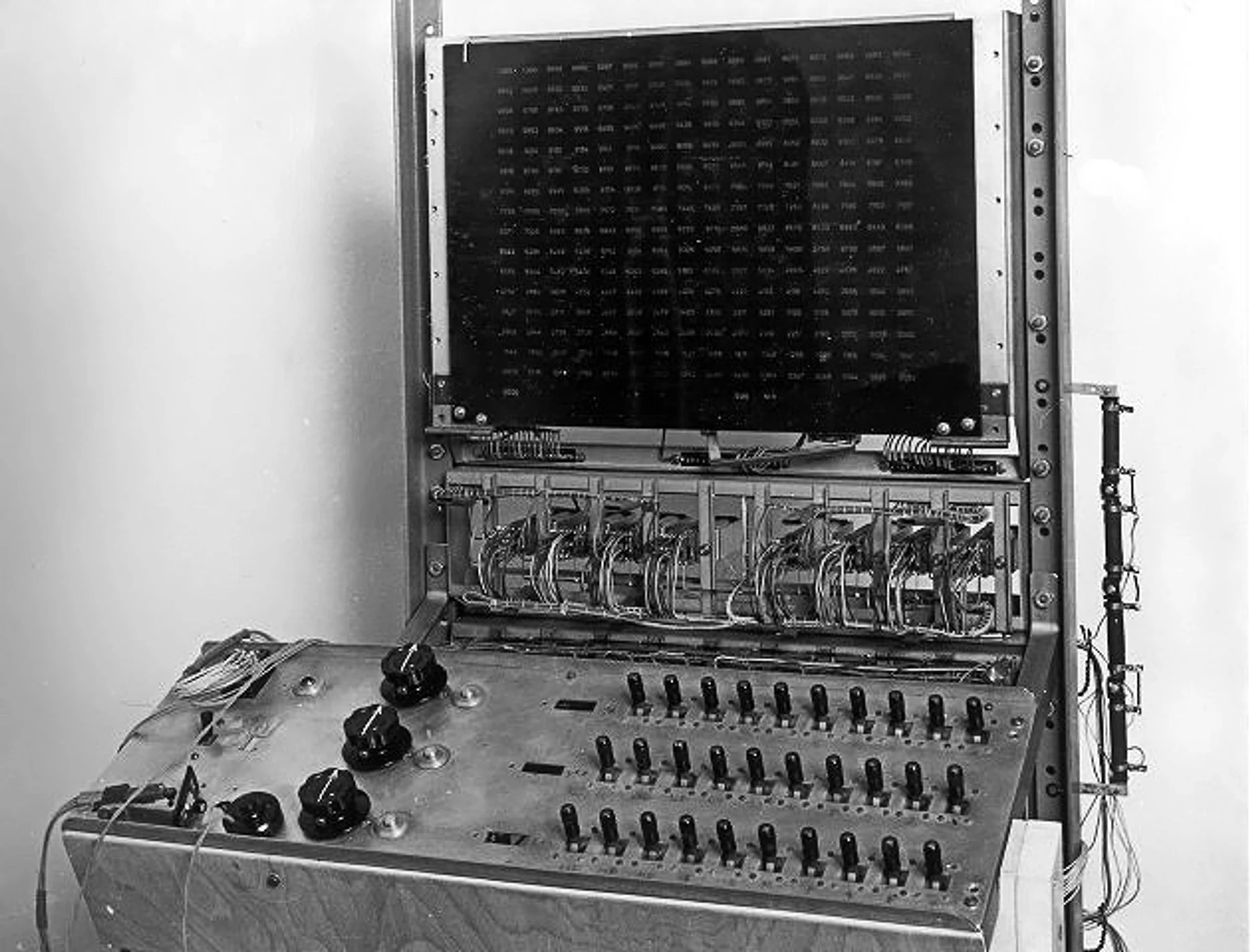

In the meantime, however, the world of computer development underwent another whirlwind of technological change. In the post-war period, just as the world was beginning to understand the potential of computers, a new project destined to change the future of computing emerged at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). True to its name, Whirlwind stirred the waters of technological progress with remarkable innovation. Its development began in 1945 under the leadership of visionary engineer Jay Forrester and was initially intended as a flight simulator for the U.S. Navy. But as so often happens with groundbreaking inventions, Whirlwind soon exceeded its original purpose. So, what made it so revolutionary? It was the first computer capable of real-time computations. In an age when most computers processed data in batches, Whirlwind responded instantly to user input. This capability opened the door to interactive computing, forever changing how people interact with computers. But that wasn’t all. Whirlwind pioneered the use of magnetic random-access memory (RAM). This technology, perfected in 1953 with the implementation of ferrite core memory, dramatically increased the reliability and speed of computers. Furthermore, the Whirlwind’s use of CRT displays for visual output laid the groundwork for future graphical interfaces. With 5,000 vacuum tubes and the ability to perform 50,000 operations per second, Whirlwind was a technological marvel of its time. Its influence extended far beyond the MIT’s labs. The technologies developed for Whirlwind were adopted by the SAGE Air Defence System and inspired the development of future computer systems. Although it originally used electrostatic memory tubes (known as Williams tubes), the implementation of magnetic memory with ferrite cores in 1953 significantly enhanced its reliability. The concept of a real-time interactive computer influenced the development of future systems. Magnetic-core memory became the standard for subsequent generations of computers and the project itself inspired the development of graphical displays and interactive interfaces. The technology developed for Whirlwind was then picked up by the TX-0 computer, an experimental transistor computer developed between 1955 and 1956. The transistor itself, a fundamental electronic component, had been invented earlier in 1947 at Bell Laboratories by a team of scientists led by William Shockley, John Bardeen, and Walter Brattain.

This revolutionary discovery made it possible to control the flow of electric current in solid matter, leading to the miniaturization of electronic devices and the launch of the modern electronics era. The transistor quickly replaced the bulky and energy-intensive vacuum tubes, paving the way for the development of smaller, more reliable, and energy-efficient electronic devices. The TX-0 had a 64K x 18-bit words of ferrite core memory and an 18-bit architecture. It only had 4 instructions, effectively making it one of the first computers with a reduced instruction set (a precursor to RISC architecture). It was also equipped with a CRT display for graphical output and a light pen to interact with the screen, which was revolutionary at the time. While it was initially programmed in machine code, assembler and other programming tools were later developed. The TX-0 served as a test platform for the development of transistor circuits and programming techniques. It also contributed to research in AI, computer graphics, and interactive computer systems. The TX-0 had a major influence on the creation of the DEC PDP-1, one of the first commercially successful minicomputers, marking the beginning of the second generation of computers.

Second Computer Generation

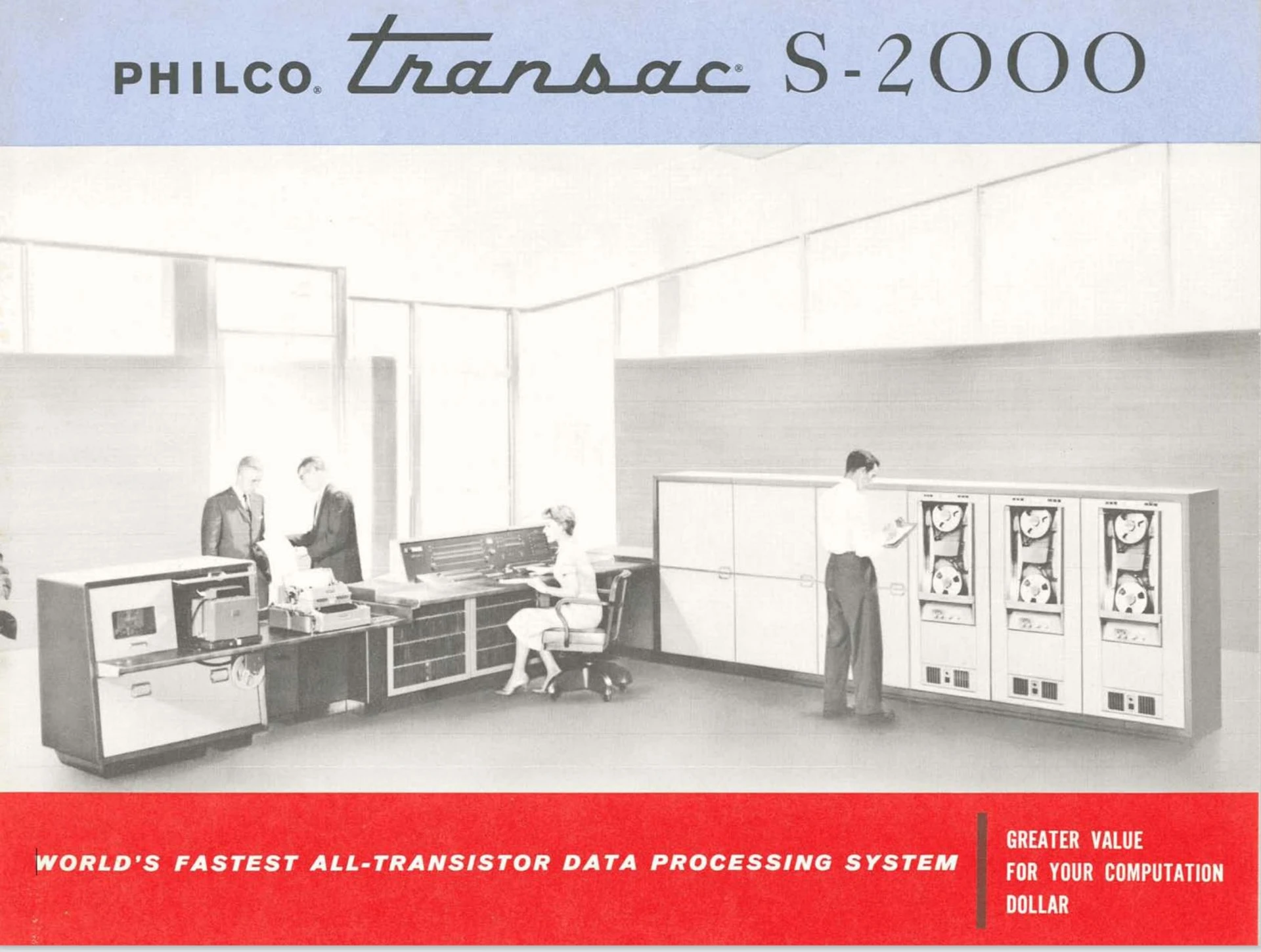

The period between 1955 and 1964 saw rapid developments in computer technology. This era, known as the transition to the second generation of computers, introduced a number of key innovations that laid the foundations for modern computing. A major breakthrough came with the introduction of transistorized computers. The first commercially available all-transistorized computer designed for scientific computing was the IBM 608, announced in 1955. Another important product of this period was the Philco TRANSAC S-2000, created by the Philco Corporation, a pioneer in consumer electronics and computing technology in the 20th century. Founded in 1892 as the Helios Electric Company, Philco gradually became a leader in radios, televisions, and home appliances. In the 1950s, the company expanded into computers, culminating in the launch of the TRANSAC S-2000 in 1958. This all-transistorized computer was designed for military and scientific purposes and was notable for its many advanced features, including parallel data processing and modular design.

The TRANSAC S-2000 symbolized Philco’s high-tech ambitions and helped solidify the company’s position as an innovator in the rapidly expanding computing industry. Although Philco later faced financial difficulties and was acquired by Ford Motor Company in 1961, the TRANSAC S-2000 remains a significant milestone in the history of computing and a testament to Philco’s technological contributions.

The year of 1957 gave us FORTRAN, the first high-level programming language that greatly simplified the programming process. The end of the decade was marked by the commercial success of the IBM 1401, which became a bestseller in the corporate world. The 1960s witnessed the advent of COBOL, a programming language specifically designed for business applications, and the DEC PDP-1, the first commercial computer with an interactive interface. The following years saw the introduction of powerful mainframes like the IBM 7090 and supercomputers such as Atlas, developed at the University of Manchester.

This era was characterised by several key trends. The switch from vacuum tubes to transistors led to smaller, faster, and more reliable computers. The development of high-level programming languages greatly facilitated programming and increased the productivity of developers. Computers began to expand from scientific and military applications into the commercial sphere, leading to the emergence of the software industry as an industry of its own.

The performance and memory of computers increased dramatically, enabling them to solve increasingly complex problems. With the appearance of the IBM System/360 in 1964, the era of standardization in the computer industry began. At the same time, the first interactive computer systems appeared, laying the foundation for future personal computers. This dynamic era transformed computing from a niche scientific discipline into a vital industry, setting the stage for the digital revolution that was yet to come. The innovations introduced between 1955 and 1964 continue to influence how we design, develop, and use computer technology to this day.

It was also the beginning of Czechoslovak computing history, which is closely linked to three pioneering machines: ELIŠKA, SAPO, and EPOS 1. These computers represented significant milestones in the development of Czechoslovak computer science and showcased the ability of local scientists and engineers to keep pace with global advancements despite limited resources and the political obstacles of the Cold War.

The first Czechoslovak automatic computer, ELIŠKA, was designed, built, and put into operation by Allan Línek at the Institute of Technical Physics of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences at the end of 1952. This dedicated punched-card relay computer was used to calculate structure factors in determining crystal structures and remained in use until the early 1960s. In 1954, Allan Línek, together with Ctirad Novák, developed another dedicated computer, SuperELIŠKA, designed to calculate electron densities.

The development of the SAPO computer (short for SAmočinný POčítač, meaning “automatic computer”) began in 1950 at the Institute of Mathematical Machines of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague. Completed in 1957, this relay computer was the first functional computer in Czechoslovakia and one of the first in Central and Eastern Europe. It contained approximately 7,000 relays and had a drum memory with a capacity of 1,024 words. Although relatively slow—executing only about three operations per second—it was designed for scientific and technical computing and was programmed using punched cards. Interestingly enough, SAPO featured an advanced inbuilt fault detection system using triple modular redundancy. Unfortunately, this pioneering machine was destroyed in a fire in 1960.

Shortly after SAPO, EPOS 1 (short for Elektronický POčítací Stroj, meaning “electronic calculating machine”) was finished in 1958 at the Research Institute of Mathematical Machines in Prague. EPOS 1 marked a significant technological leap forward. As a vacuum-tube computer with about 3,000 tubes, it was significantly faster than its predecessor, capable of executing about 5,000 operations per second. It featured a ferrite memory with a capacity of 1,024 words (40 bits) and was initially programmed in machine code. Later, an assembler program was developed for it. EPOS 1 was used for practical purposes, such as calculations for the construction of the Czech Orlík Water Reservoir, and it served as the basis for developing other computers in the EPOS series.

Although technologically different, these two computers laid the groundwork for further computer development in Czechoslovakia. While less technologically advanced, SAPO stood out for its innovative fault detection system. EPOS 1, on the other hand, demonstrated the ability of Czechoslovak experts to quickly switch to more advanced vacuum-tube technology. The significance of SAPO and EPOS 1, however, goes beyond their technical specifications. They inspired a new generation of computer scientists and engineers and proved that Czechoslovakia could develop its own advanced technologies. And such, they became symbols of the early days of Czechoslovak computer science and a testament to the innovative spirit of local experts, even during a time when the global political climate hindered their access to the latest Western technologies.

Digital Revolution

This is where our journey through the history of computers ends for now. Whether we like it or not, we have long since entered the age of the digital revolution. The transformation it has brought to the world is more profound and far-reaching than, for instance, the invention of the printing press. And while it’s impossible to fully capture the vast scope of this technological transformation here, I hope this quick foray into the history of computing inspires you to reflect on the never-ending evolution of human knowledge—and to consider how powerful a tool we have been given in just a few decades.

Key Milestones in the Development of Computing

ca. 2400 BC: Abacus (the first known counting machine) – Babylonia

ca. 100 BC: Antikythera mechanism (an ancient analogue computer) – Ancient Greece

1617: Napier’s bones (a multiplication aid) – John Napier

1642: Pascaline (the first mechanical calculator) – Blaise Pascal

1673: Stepped Reckoner – Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

1801: Punched cards for controlling looms – Joseph Marie Jacquard

1822: Difference Engine (only a model) – Charles Babbage

1837: Analytical Engine (a concept of the first programmable computer) – Charles Babbage

1843: First computer program – Ada Lovelace

1890: Electromechanical Tabulating Machine – Herman Hollerith

1936: Turing Machine (a theoretical model of computation) – Alan Turing

1937–1942: ABC (Atanasoff-Berry Computer) – John Vincent Atanasoff and Clifford Berry

1941–1945: Z3 (the first fully functional programmable computer) – Konrad Zuse

1943–1945: Colossus (the first electronic digital computer) – Tommy Flowers

1945: ENIAC (the first electronic general-purpose computer) – J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly

1947: First working transistor – William Shockley, John Bardeen, and Walter Brattain

1949: EDSAC (the first practical stored-program computer) – Maurice Wilkes

1951: UNIVAC I (the first commercially produced computer) – J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly

1953: IBM 701 (the first commercially successful scientific computer)

1954: FORTRAN (the first high-level programming language) – John Backus

1955: IBM 608 (the first commercially available all-transistorized computer)

1958: First integrated circuit – Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce of “Texas Instruments”

1959: COBOL (a programming language for commercial applications) – Grace Hopper and the CODASYL committee

1960: DEC PDP-1 (the first commercial minicomputer) – Digital Equipment Corporation

1964: BASIC (a programming language for beginners) – John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz

1969: ARPANET (a precursor to the Internet) – DARPA

1971: Intel 4004 (the first commercially available microprocessor)